Andy Warhol University

Whether you’re in Pittsburgh for business, pleasure, or a roundtable discussion about the growing role of analytics and Big Data in higher education, it’s worth a trip to The Andy Warhol Museum. How much is it worth? That’s difficult to quantify—unless you get the student or member discount. But if you’re a fan of qualitative value you can walk along the Allegheny River, cross one of the city’s striking, 1920s era Three Sisters bridges (I went over on the Rachel Carson but returned on the Andy), and head to the museum’s seventh floor to explore the life and artistic accomplishments of Pittsburgh’s native son.

The experience provided me with a deeper appreciation for Warhol’s talent and extensive body of work, as well as some lessons his career has to offer for the future of higher education.

The Promise

Andrew Warhols’s working-class parents were first generation Slovakian immigrants, and he spent his earliest years in a two-room apartment without indoor plumbing. But because his parents valued education and encouraged his artistic pursuits, Andy went on to earn a Fine Arts degree from the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University). He then moved to New York and became one of his generation’s most successful commercial artists. (Consultants take note: after meeting with a new client, Andy would return the next day with 50+ concept sketches.)

It’s a classic American story—one that makes a compelling case for the Return-On-Investment (ROI) from a Carnegie Mellon arts degree. But it also highlights a key reason why we invest in higher education: for its life-changing potential and promise. The value of Andy Warhol’s education was far more than how much he was able to earn after it was over. The learning process and the experiences and relationships it provided had a transformative impact on his life and art. It would be interesting to know whether his parents could afford to make that same promise today.

The Factory

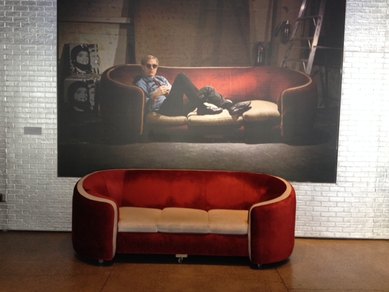

While perhaps best known for its celebrity fueled all-nighters, Warhol’s New York studio was the ultimate flipped classroom and maker space. Its brick walls covered in foil and silver paint, the Factory created a dynamic learning environment that encouraged investigation, experimentation, collaboration, mentorship, social interaction and cohesion, entrepreneurship and interdisciplinarity. It even served as a de facto living-learning community, with its famous couch hosting many of the 1960s’ leading visual artists, designers, actors, writers, musicians, models and drag queens. All you need are a few biochemists or doctors of business administration in the mix and you start to generate academic rigor.

The Factory’s innovations sprang from Warhol’s relentless productivity and his eagerness to try out new techniques and new technologies in a highly collaborative setting. Not to mention his ability to attract interesting people. But perhaps the biggest lesson for higher education is the way he creatively engaged the aesthetics of mass production and mass communication. Warhol actively embraced nontraditional artistic media, including film, video and television. If MOOCs and online learning are pushing higher education in more mediated directions, there’s no reason we can’t approach this with style and entrepreneurial flair, and explore the opportunities for enhanced personal expression within the new, mass-educational landscape.

The Office

No one can say Andy’s business model didn’t work—especially later in his career when he was producing high-priced portraits for international superstars. Warhol was always unapologetic about his commercial success, but something changed after he survived a shooting in 1968. He faced his mortality, and decided he needed to make as much money as possible while clients were still willing to pay a premium for his work. The Factory became the Office—and the art wasn’t quite as inspired. Still highly lucrative, but more mildly influential and increasingly self-referential—culminating in his extensive, personal archive of Time Capsules.

Late Warhol isn’t an exact analogy for the arc of higher ed. Our leading institutions of higher learning aren’t going to guest star on The Love Boat. However, you still get the sense that some institutions will be content using their brand recognition to get top dollar from an elite clientele for a well-executed product that appreciates reliably over time, while other institutions will struggle to deliver on the larger democratic promise. Not the Ivory Tower as much as a Glass Tower with a penthouse apartment, a doorman, and a concierge. Which is nice work if you can get it.

“Always leave them wanting less.”

It’s OK to have your audience think that a 12-minute film of attractive twenty-somethings slowly eating bananas is 6 minutes too long. Or that Elvis (Eleven Times) might be more Elvis than you actually need. It’s similar to serving an individual a sandwich that could feed three people at a restaurant; oversized portions have greater perceived value—even if you’re not crazy about the food. But what if your customers want more for less?

It’s doubtful whether higher education can give its customers better results with less public funding and also keep its price down without laying off a few degree programs along the way. I couldn’t help but interpret Warhol’s 1985 piece Raphael Madonna-$6.99 as the current ROI valuation of art history: the screen-print poster child for the subjects that we might not be able to afford to teach or major in anymore. Is this what it means to be left wanting less? And if so, who’s doing the leaving?

It would be great if Andy could help us predict something bold about higher education. For example “In the future, every student will satisfy their General Education requirement online in 15 minutes.” But in the end bold predictions aren’t as important as the working example set by Warhol’s groundbreaking experimentation, collaborative spirit, and prolific output. As well as the idea that “disruptive innovation” can be kind of fun.