The Expanding Role of Landscape Architects in Urban Waterfront Design

Lowland Park on Detroit’s urban riverfront, is part of the second phase of Milliken State Park, Michigan’s first state park in an urban setting.

As urban waterfronts throughout the world continue to transform from industrial centers and transportation hubs to mixed-use destinations, SmithGroup's Tom Rogers discusses how landscape architects can and should play an expanded role in shaping the future of cities.

Urban waterfronts throughout the world are transforming from industrial centers and transportation hubs to mixed-use destinations. As population growth shifts to urban centers, greater pressure to redevelop underutilized land at the water’s edge is requiring cities to address complex challenges. The most holistic solutions require a thoughtful approach at an urban scale that melds many disciplines. These waterfront projects involve a variety of stakeholders with diverse needs, and require complex, time consuming processes and significant investments in capital resources.

Landscape architects can and should play an expanded role in these significant opportunities to shape the future of cities. To do so, L.A.s must adapt and develop skillsets beyond their traditional focus to lead integrated, resilient design solutions.

In the Fall of 2018, SmithGroup, hosted a roundtable discussion with clients and colleagues from Rust Belt communities throughout the Great Lakes to discuss the challenges and opportunities for their urban waterfronts. Attendees included representatives from municipal planning departments, regional watershed districts, redevelopment authorities, regulatory agencies, private developers, nonprofits, and the Great Lakes St. Lawrence Cities Initiative.

While each of the participants represented a unique vantage point, they painted a striking similar picture of the issues; shifts in markets and policy have resulted in economically challenged neighborhoods next to underutilized, often contaminated industrial property near the core of their cities. Many of these properties are located on or near water. The problems involve a tangled web of owners, users, regulators and policies that cannot be addressed solely though site-specific solutions but must be approached at a larger scale to be effective.

Performance, partnerships and equity emerged as key themes and design drivers during our discussion, pointing to the more integrated and resilient solutions required to return our urban waterfronts to the right balance of public use, environmental integrity, and prosperity.

Performance

In many cities, urban waterfronts represent the most valuable space, and the best opportunity for growth and change for the next 100 years. There is significant pressure to prove the performance of these spaces with measurable outcomes. As one of the participants stated, “We are spending billions of dollars on cleanup of contaminated sites. How do we make sure we are spending it to add value, instead of just treading water?” To create transformational results, landscape architects must prove the value of their solutions as performance landscapes, demonstrating that performance with empirical evidence.

Lowland Park on Detroit’s urban riverfront is an example of a performance-based solution. Once a brownfield site, the 6.1 acre parcel is the second phase of Milliken State Park, Michigan’s first state park in an urban setting. The project features interpretive displays, restored native habitat, and a wetland that treats runoff from 12.5 acres of adjacent parcels. In addition, it provides recreational space for more than 1,000,000 visitors per year and generates over $5.8 million annually in economic activity from visitors spending.

Lowland Park is part of a larger riverfront revitalization effort that has included the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy, the City of Detroit, and countless partners, to lay the groundwork for revival along the urban waterfront. The Detroit Riverfront Conservancy has tracked economic impact over time to demonstrate how the bold vision has led to over $1 billion in public and private investments. The Detroit RiverWalk was recently named as one of the best city walks in the world by the Guardian (UK), another indicator of design performance.

Partnerships

Urban waterfront challenges are often large in scale, involving a multitude of property owners with sometimes competing agendas. In addition, decreasing funding at the public level means the private sector must be engaged to support comprehensive solutions. Forming partnerships is essential to creating successful solutions. Wide-ranging partnerships generate more opportunities to address community-scale problems and access unique funding sources, from securing private capital to state and regulatory grant monies. They also create a foundation of project advocacy and support that can be maintained over time. Many projects lose momentum with a change in administration, but a partnership-based approach can transcend election cycles to bring a project to fruition.

The City of Euclid, Ohio provides an example more than 10 years in the making. Euclid stretches along the shore of Lake Erie east of Cleveland for nearly four miles. Yet much of the shoreline has been inaccessible to the public, with severe bluff erosion threatening adjacent homes and development. Landscape architects helped lead an engagement process that resulted in a cooperative approach between the City and nearly 100 private land owners. The resulting project will create nearly one mile of public access along the lakeshore, while improving surrounding habitats and protecting adjacent properties from further shoreline erosion. The solution was built on finding common ground that resonated with all stakeholders, yielding results far beyond what smaller, individual projects would have been able to accomplish.

Equity and Inclusion

Equity has emerged as a key issue for urban planning and design projects, and was a frequent topic of conversation during our roundtable. Residents and business owners don’t always have a voice at the table when decisions are being made about the future of their community. Barriers related to income, race, age, and language frequently contribute to this. As a result, many neighborhoods lack the amenities and connectivity they should have. In other cases, the proposed improvements lead to neighborhood gentrification, and the displacement of people who can no longer afford to live in that part of the city.

Truly equitable engagement in the planning and design process can be challenging, requiring key partners and substantial time to establish trust. However, when done well an inclusive approach results in holistic solutions that serve cities in more equitable ways. They address key problems, from providing better transportation connections to creating civic engagement and educational opportunities that promote more comprehensive economic, social and environmental well-being.

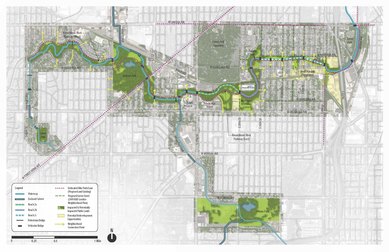

The Kinnickinnic River Corridor Neighborhood Plan in Milwaukee, WI, was the result of a unique partnership between Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, Sixteenth Street Community Health Center, and the City to develop a community-based plan for a revitalized and reconnected river and neighborhood. The plan was an integrated part of removing the concrete channel encapsulating the river to increase flood capacity and meet public safety objectives by creating a wider, naturalized footprint. To accommodate this, nearly 100 homes needed to be removed from this predominantly low-income neighborhood.

An extensive, multilingual public outreach process engaged local residents and business owners to envision how the expanded Kinnickinnic River could serve the community in a positive and meaningful way. It created a framework for both the river and the neighborhood, integrating a series of projects that address stormwater and flooding while rehabilitating existing housing stock, identifying redevelopment opportunities, improving local commercial corridors, creating better parks and open space, and providing programming opportunities that positively benefit the neighborhood. Ongoing projects, such as the Kinnickinnic River and Jackson Park Restoration, are focused on creating additional flood storage capacity along this urban watershed in ways that engage and enhance the adjacent neighborhoods.

More than the Sum of Its Parts

As cities work to adapt to economic challenges as well as climate change, the design of our urban waterfronts must be approached with a resiliency mindset that goes beyond addressing individual site design and explores systems that create larger scale benefits. Landscape architects can play a larger role in these complex, integrated efforts by expanding their traditional design focus and skill sets. The ability to support more equitable community engagement, develop measurable, performance-based solutions, and help forge committed public/private partnerships will play a pivotal role in the design legacy of urban waterfronts.

This piece was originally published in The Field, the American Society of Landscape Architects practice networks blog.